art, pop culture

Art Stories And Artists Of The 2010s Decade

A billboard posted outside Lisson Gallery in London in 2011, calling for Ai Weiwei to be released from detainment.MATT DUNHAM/AP/SHUTTERSTOCK

Ai Weiwei arrested for calling for freedom of expression in China in 2011.

Art Stories And Artists Of The 2010s Decade

In 2011, Ai Weiwei was arrested on suspicion of “economic crimes” at Beijing Capital International Airport, just moments before he was to catch a flight to Hong Kong. Meanwhile, some 20 police officers searched his studios. There was an instant backlash from the international arts community, with critics alleging that his detainment was retribution for his repeated calls for democracy in China. Ai had just been announced runner-up for the TIME magazine Person of the Year, and he was suddenly more visible than ever. The United States and the European Union protested his detention, as arts institutions worldwide held demonstrations.

“Release Ai Weiwei” was emblazoned on the side of Tate Modern, while 90,000 people signed a petition organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and the International Council of Museums demanding Ai’s release. In Hong Kong, artists created a series of street art protests against Ai’s incarceration, leading to further arrests. After 81 days in captivity, Ai was released. He didn’t give up his protests, however—in the intervening years, he has continually called for greater freedom for artists in China and far beyond.

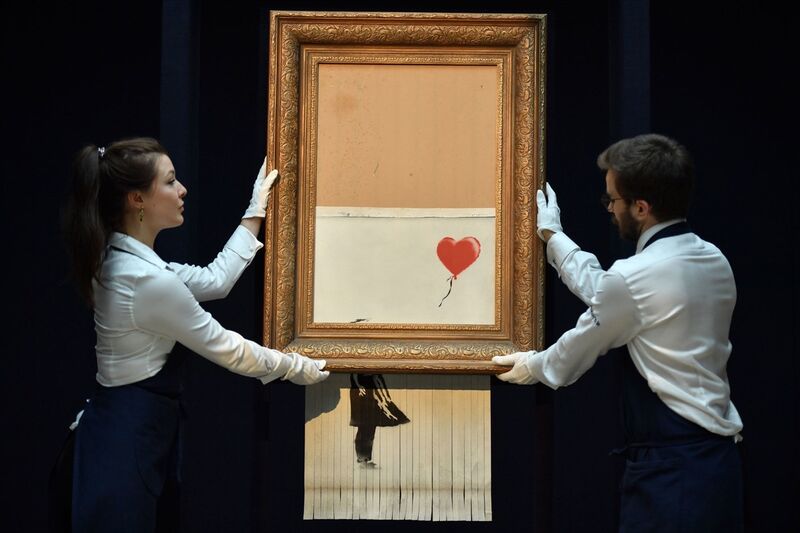

Banksy

Origin Of The Universe By Mickalene Thomas

Origin of the Universe, Thomas’s first solo museum exhibition, highlights recent bodies of work that examine interior and exterior environments in relation to the female figure. Their settings are often inspired by her 1970s childhood.

Thomas’s production is informed by the classical genres of portraiture, landscape, still life, and the female nude. She combines careful borrowings from historical painting with contemporary popular culture, taking cues from such artists as Romare Bearden, Gustave Courbet, David Hockney, Édouard Manet, and Henri Matisse. In combining traditional genres with African American female subjects, Thomas makes a case for opening up the conventional parameters of art history and culture. Among the pieces on view are contemporary riffs on Courbet’s Origin of the World and Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe. Seventy-five of the ninety featured works were added for the Brooklyn presentation. An entrance-gallery mural, a film about Thomas’s mother, and installations of furnished domestic interiors were created specifically for this show.

Mickalene Thomas: Origin of the Universe was organized by the Santa Monica Museum of Art and Lisa Melandri, former Deputy Director for Exhibitions and Programs. The Brooklyn presentation is organized by Eugenie Tsai, John and Barbara Vogelstein Curator of Contemporary Art, Brooklyn Museum.

New York-based artist Mickalene Thomas is best known for her elaborate paintings composed of rhinestones, acrylic and enamel.

Mickalene Thomas (lives and works in Brooklyn, NY) makes paintings, collages, photography, video, and installations that draw on art history and popular culture to create a contemporary vision of female sexuality, beauty, and power. Blurring the distinction between object and subject, concrete and abstract, real and imaginary, Thomas constructs complex portraits, landscapes, and interiors in order to examine how identity, gender, and sense-of-self are informed by the ways women (and “feminine” spaces) are represented in art and popular culture.

Thomas has been awarded multiple prizes and grants, including the USA Francie Bishop Good & David Horvitz Fellow (2015); Anonymous Was A Woman Award (2013); Brooklyn Museum Asher B. Durand Award (2012); and the Timerhi Award for Leadership in the Arts (2010).

The 2014 Whitney Biennial.ANDREW GOMBERT/EPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

A Whitney Biennial withdrawal initiates a conversation about race (2014)

The decade’s Whitney Biennials sparked a number of debates about race and representation—the most notable perhaps centering on Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket in the 2017 edition. But the 2014 show—the last one staged in the Whitney’s former home in Uptown Manhattan—set the stage for those later events, with a group of black artists known as the Yams Collective pulling out of the show in protest. The issue for the group, which was appearing under the name HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, was the presence in the exhibition of Joe Scanlan, a white male artist who was presenting work that he billed as being by Donelle Woolford, a fictitious artist who was an African-American woman played in performances by actors.

“We felt that the representation of an established academic white man posing as a privileged African-American woman is problematic, even if he tries to hide it in an avatar’s mystique,” Maureen Catbagan, one of the group’s members, told Hyperallergic. Scanlan, for his part, said that the efforts involved in the project had been “some of the most intellectually challenging and humanly rewarding experiences of my life, largely because it has required me to confront what I don’t know, come to grips with those limits, and work at pushing them, expanding them.”

In this painting, Kehinde Wiley boldly recasts Napoleon as a contemporary black warrior. In his reference to Jacques-Louis David’s painting Napoleon Bonaparte Crossing the Alps at Great St. Bernard Pass, Wiley creates a tension with traditional art history and its neglect of black subjects. His portrait symbolically reassigns value to the sitter, asking us to recall remarkable black leaders such as Toussaint L’Ouverture from Haiti, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Nelson Mandela, whose images appear far less frequently, if at all, in histories of art.

—Tumelo Mosaka, independent curator

KEHINDE WILEY: A NEW REPUBLIC

The works presented in Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic raise questions about race, gender, and the politics of representation by portraying contemporary African American men and women using the conventions of traditional European portraiture. The exhibition includes an overview of the artist’s prolific fourteen-year career and features sixty paintings and sculptures.

Wiley’s signature portraits of everyday men and women riff on specific paintings by Old Masters, replacing the European aristocrats depicted in those paintings with contemporary black subjects, drawing attention to the absence of African Americans from historical and cultural narratives.

The subjects in Wiley’s paintings often wear sneakers, hoodies, and baseball caps, gear associated with hip-hop culture, and are set against contrasting ornate decorative backgrounds that evoke earlier eras and a range of cultures.

President Portrait By Kehinde Wiley

Exhibition Label: Forty-fourth president, 2009–2017

Barack Obama made history in 2009 by becoming the first African American president. The former Illinois state senator’s election signaled a feeling of hope for the future even as the U.S. was undergoing its worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

While working to improve the economy, Obama enacted the Affordable Care Act, extending health benefits to millions of previously uninsured Americans. Overseas, he oversaw the drawdown of American troops in the Middle East—a force reduction that was controversially replaced with an expansion of drone and aviation strikes.

Though his mission to kill al-Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden was successful, his pledge to close the Guantanamo prison went unrealized.Artist Kehinde Wiley is known for his vibrant, large-scale paintings of African Americans posing as famous figures from the history of Western art.

This portrait does not include an underlying art historical reference, but some of the flowers in the background carry special meaning for Obama. The chrysanthemums, for example, reference the official flower of Chicago. The jasmine evokes Hawaii, where he spent the majority of his childhood, and the African blue lilies stand in for his late Kenyan father.

At center, Ann Freedman, the former director of Knoedler & Co. gallery in New York.SETH WENIG/AP/SHUTTERSTOCK

America’s oldest gallery shutters amid a string of lawsuits (2011)

It was a scandal that shocked the art world and spanned the full decade. Knoedler gallery president Ann Freedman actually exited her post right before the decade began, in October 2009, after the gallery was accused in a lawsuit of selling fake Robert Motherwells. Soon, more whispering would begin that the oldest gallery in America had been selling forged paintings attributed to postwar abstractionists for tens of millions of dollars. Knoedler shuttered in 2011, but the legal saga was just beginning. The FBI investigated and ended up charging a Long Island art dealer, Glafira Rosales, with orchestrating the scheme with her longtime partner, Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz, and the painter Pei-Shen Qian, who allegedly made the fakes. Rosales pleaded guilty. The other two remained outside the country. Freedman was never accused of criminal wrongdoing and, along with other civil defendants, ended up settling a string of lawsuits from collectors, the last of which closed earlier this year. It reinforced an old adage for collectors: even at the most august institutions, caveat emptor.

Installation view of “Anicka Yi: 7,070,430K of Digital Spit,” 2015, at Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland.PHILIPP HÄNGER/COURTESY 47 CANAL, NEW YORK AND KUNSTHALLE BASEL, SWITZERLAND

Anicka Yi, Maybe She’s Born with It, 2015

Throughout the first half of the decade, Anicka Yi established herself as one of the most venturesome artists of the present moment, experimenting with ephemeral materials and scents to conjure delirious work that touches on geopolitics, memory, and identity. Her 2015 show at the Kunsthalle Basel in Switzerland saw her inimitable visions ascend to a whole new level, and this sculpture—a column of tempura-fried flowers encased in a glowing bubble—exemplifies her achievement, suggesting an artwork as a living, breathing thing, perhaps on life-support, perhaps being cultivated into something new and grand, seductive and terrifying. I’ll never forget the electrifying moment that I first saw it. At the time, we had no idea then of just how ambitious and incisive Yi’s work would become, but this was clear sign that big things were on the horizon. —Andrew Russeth

Parker Bright protesting Dana Schutz’s Open Casket.

Dana Schutz’s Open Casket Painting

Dana Schutz’s Open Casket (2016), a controversial painting currently on view in the Whitney Biennial that features an abstracted view of Emmett Till’s open casket funeral. The Whitney has since updated the label for the work, acknowledging the protest and including a statement from Schutz, and on April 9, it will host “Perspectives on Race and Representation,” an event held by poet Claudia Rankine and her Racial Imaginary Institute that takes the controversy as its starting point.

Amy Sherald, Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, 2018, oil on linen.MARK GULEZIAN/NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

5. Amy Sherald, First Lady Michelle Obama, 2018

When Amy Sherald’s luminous portrait of Michelle Obama debuted at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. in February 2018, the artist was relatively little known. Her intimate work would quickly change that. The former First Lady is seated before a light blue backdrop, donning a flowing dress patterned with dynamic shapes and abstract formations. The details captivate, like her lustrous purple polish, carefully rendered on the subject’s fingernails. Since the work’s unveiling on the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s 209th birthday, the artist has won the Pollock Prize for Creativity and joined the powerhouse gallery Hauser & Wirth, with whom she recently had a lauded solo exhibition in New York. —Claire Selvin

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, 2014.RICHARD DREW/AP/SHUTTERSTOCK

2. Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, 2014

The sculpture’s physicality immediately overwhelmed when one entered the former Domino Sugar factory in Brooklyn: it was 75 feet long and 35 feet tall, with 80 tons of polystyrene coated in white sugar. The densely layered historical allusions took more care to unpack. Sugar Baby dominated a hall of the refinery, the spot of one of the city’s longest labor strikes, and the factory was slated to be demolished after the exhibition for condominiums. The air smelled of burnt sugar and molasses dripped from the ceiling. The boldly female sphinx-like figure was given the features of a Black “mammy,” the antebellum-era stereotype employed by manufacturers for molasses and other products, here reimagined as an irrepressible force. It was an indictment of the enduring vestiges of racial exploitation, blown up to discomfiting scale. Some viewers were offended, others moved. Though it was destroyed at the end of its run, it remains an indelible, unforgettable work—a piece people will be talking and arguing about for decades to come. —Tessa Solomon